Camellia Sinensis

All tea comes from the Camellia Sinensis plant. (See https://theswissteasommelier.com//tea-talk/).

This is a good start, but as is often the case in life, the situation is trickier than this. In fact, it is really complicated. The two basic varieties of the Camellia genus (This taxonomic rank in the Theaceae family covers several hundred original plants and several thousand hybrids, among which there is our Camellia garden plant) are Camellia Sinensis var. Sinensis and Camellia Sinensis var. Assamica. Only vegetative propagation (Let’s say ‘cloning’ by cutting off a branch and planting it to start a new bush) preserves the original plant’s characteristics. Developing new plants from seeds – which never reproduce exact copies of their parent plants – will, however, lead to slight deviations. If these turn out to be successful, new cultivars can be developed.

There are various highly fascinating cultivars, such as B157 (Developed at Bannockburn Tea Garden in India), P312 (Phoobsering Tea Plantation) or AV2 (Ambari Vegetative). Some of these are favored for their drought tolerance while others are popular due to their high yield. AV2 has a particularly intriguing distribution of water in its leaves – The water is not uniformly distributed to the edge of the leaves. Instead, most water is kept close to the stem -, which leads to two differently colored kinds of flakes during the production of tea leaves. This makes for a highly appealing “mix” of tea leaves in your tin.

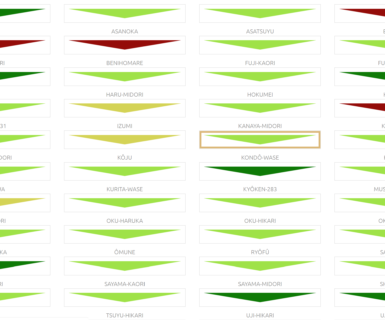

The Japanese, too, have experimented a lot with cultivars and have found some that start early or late in the year. Combining the two allows harvest and delivery of tea fresh from the field for a much longer period than if only one kind were sold. Other cultivars appear to lend themselves more to being processed into matcha than sencha, while yet another group is more blight resistant. In Japan, cultivar registration began around 1950, and more than 80 different kinds have been certified since then.